Mapping Mars

Growing up in Colorado meant summers spent hiking the Rockies. Elbert, Yale, Quandary, Princeton—each summit was its own battle, each climb a slow, deliberate ascent. Pikes Peak, I’ll admit, I’ve only “conquered” by train and by car (twice), but the rest? Grueling step after grueling step, pushing past the tree line, wading through icy runoff, scrambling over boulder fields, only to crest a false summit and realize there was still more to go.

At some point on every hike, I’d ask the age-old question: Are we there yet? My dad, ever patient, stopped answering and just handed me the map. He’d point to where we were, trace where we were headed, and let me connect the dots.

That was my first real introduction to reading topographic maps—seeing the land not just as a backdrop but as something tangible, something with shape and depth. The contour lines weren’t just lines; they were ridges, valleys, cliffs, and slopes. And I learned fast: if the lines are packed together, brace yourself—it’s about to get steep.

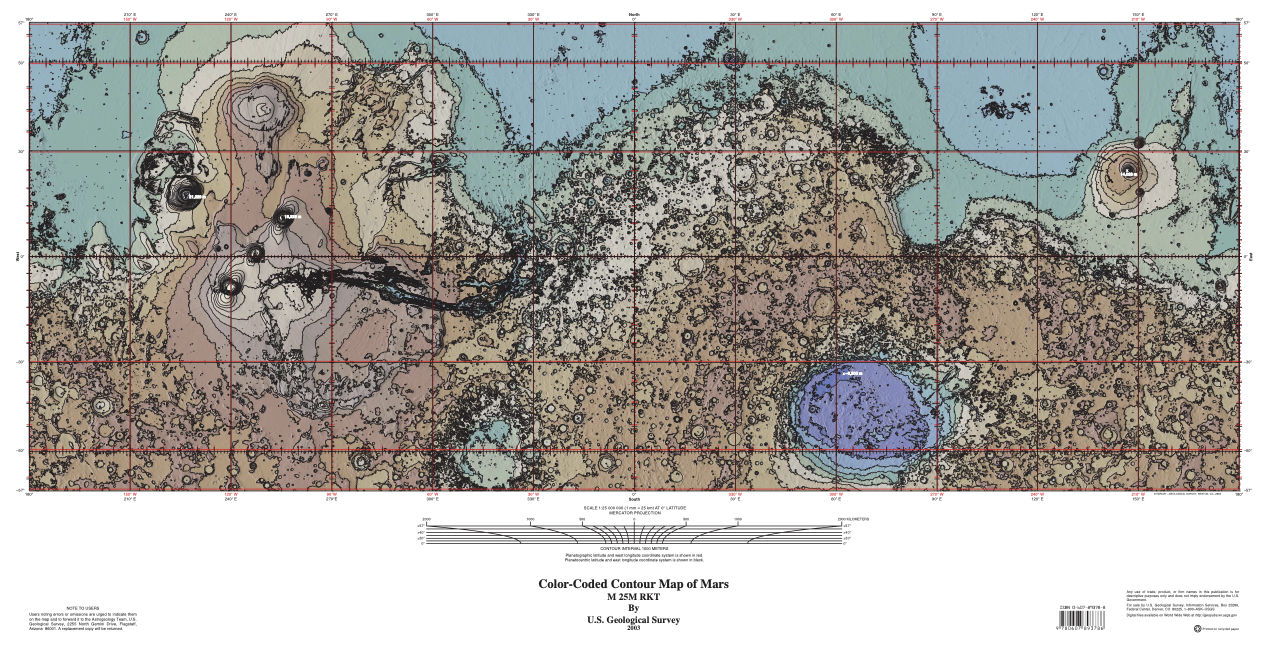

So when I started working on my map for Martian Alchemist, that experience came rushing back. What if I built my map using real Martian topography as the foundation?

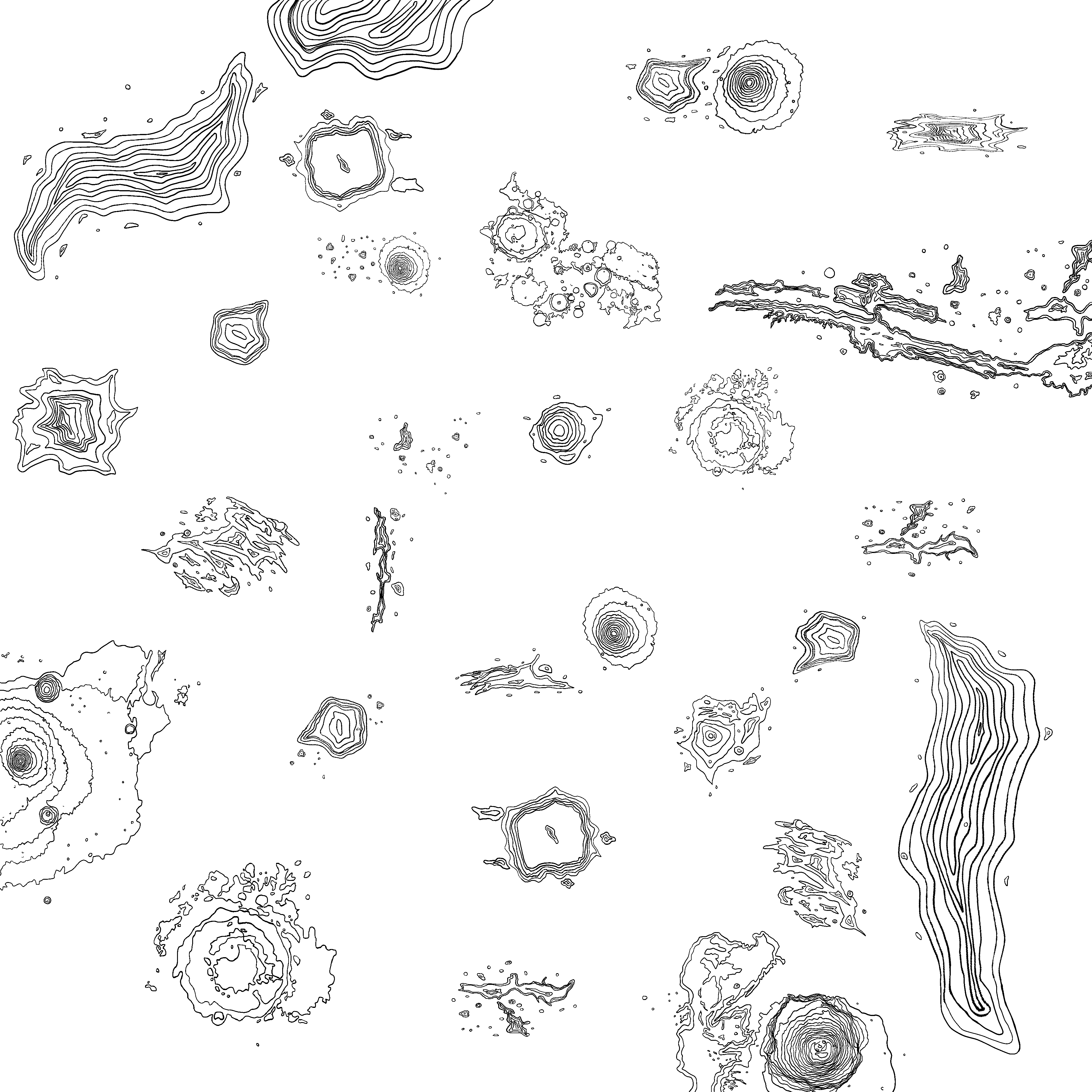

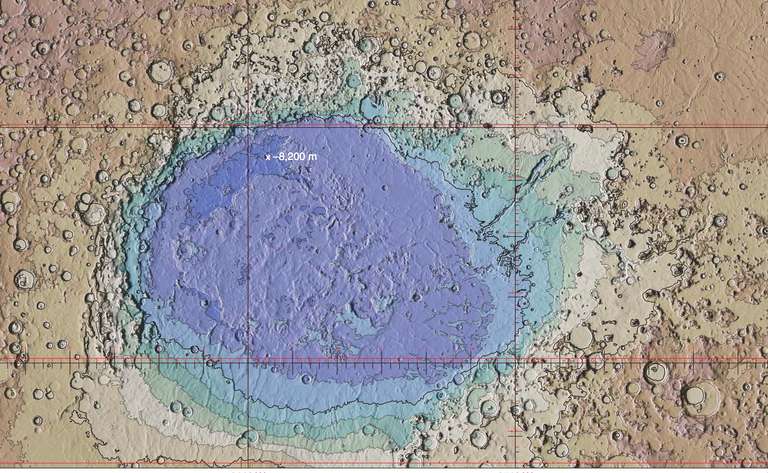

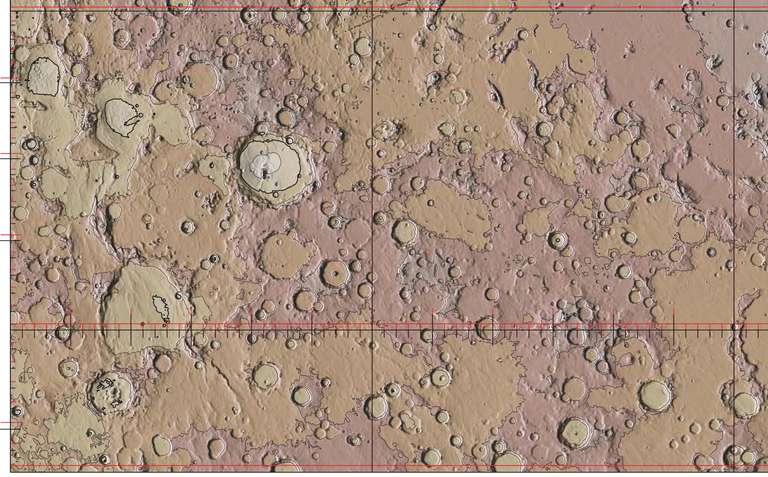

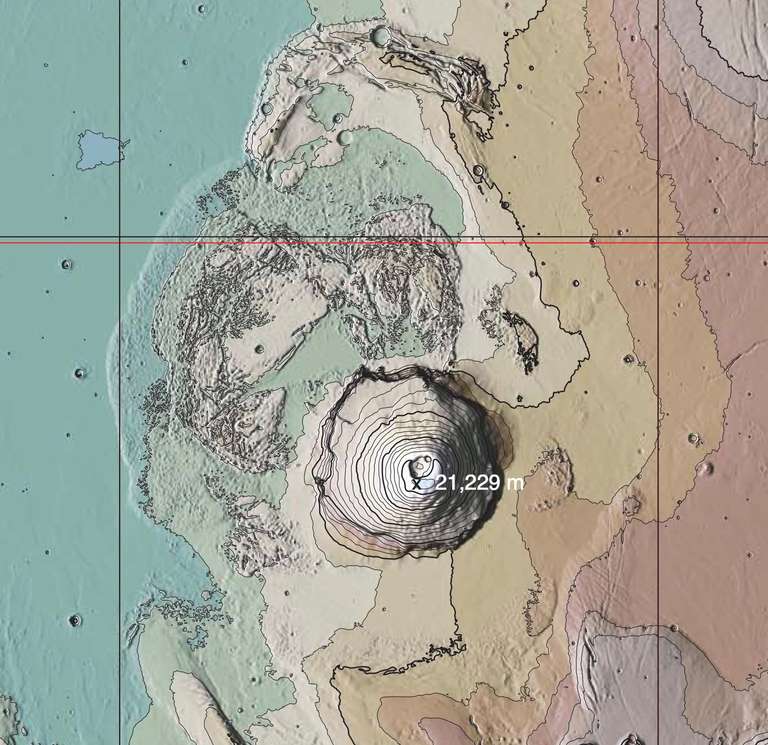

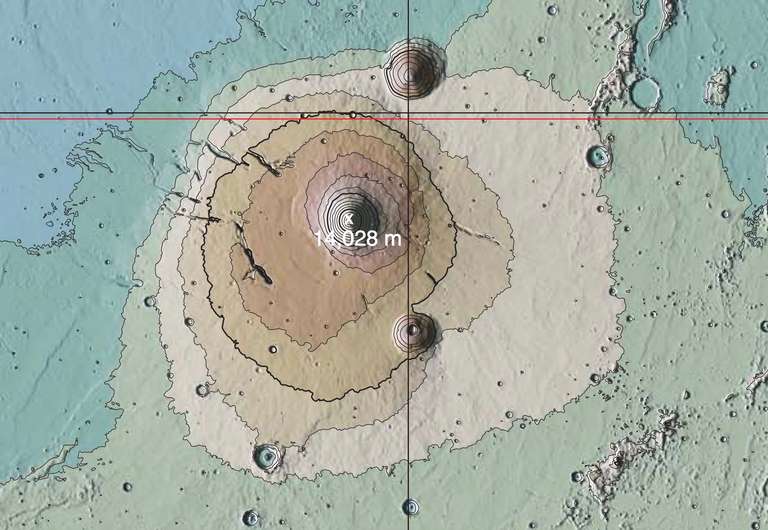

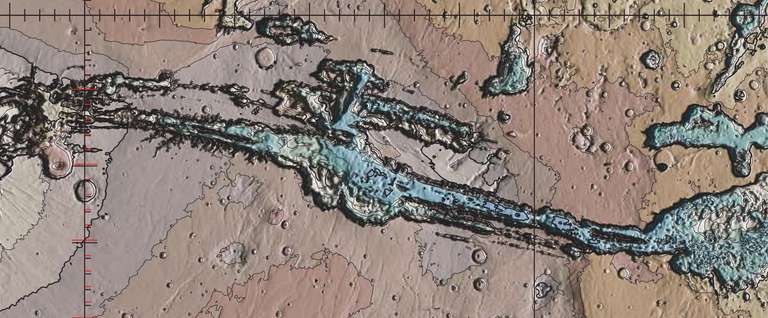

That thought sent me down a rabbit hole of Martian elevation data, tracing ancient riverbeds, marking impact craters, and mapping out the towering volcanoes that define the planet’s surface. Mars doesn’t have forests or oceans, but it does have Olympus Mons—nearly three times the height of Everest—and Valles Marineris, a canyon system so vast it makes the Grand Canyon look like a crack in the pavement. The more I explored, the more I realized these natural formations weren’t just interesting—they were the perfect way to structure hazard zones.

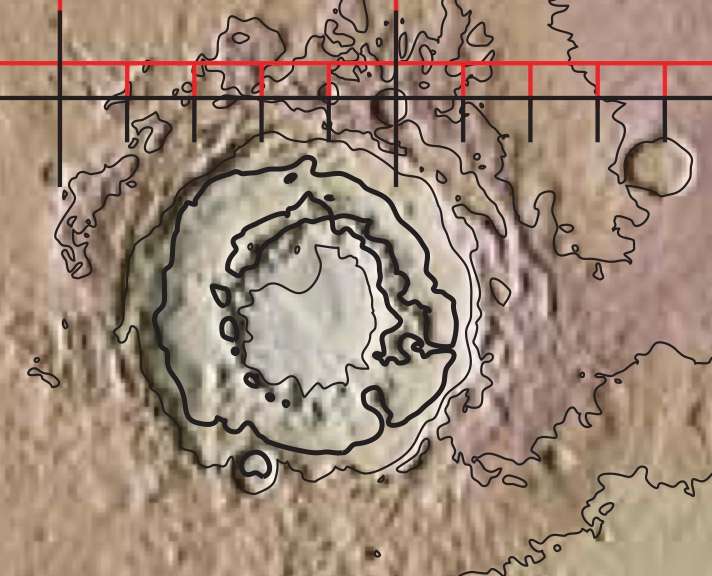

So I started layering. Elevation changes, natural barriers, places where the terrain could naturally create choke points or safe havens. I stylized and simplified where needed, but at its core, this is real Martian geography. The map isn’t finished yet, but I love where it’s heading. There’s something satisfying about knowing these aren’t just arbitrary landforms—they exist. They’ve been shaped by time, impact, and erosion, and now, in some small way, they’re shaping my world too.

One of the most fun parts of building this game has been injecting little pieces of my life into it. The map, of course, pulls from my childhood spent hiking and love of topographic maps, but it goes deeper than that. There are details tucked into the game that might not mean much to anyone else, but to me, they feel like home. From subtle nods to my favorite childhood worlds to small inside jokes embedded in the code, it’s the kind of personal touch that makes indie games so special.

And, yes, I’ve even hidden some Space Cats easter eggs in there. Because why not? If I’m going to spend this much time in a world of my own making, I want it to feel like mine. That’s one of my favorite things about indie games—they’re almost always deeply personal. Whether it’s a game’s art style, its mechanics, or its storytelling, there’s usually a person (or a small team) behind it, leaving little breadcrumbs of themselves throughout the experience. It’s that handcrafted, heart-on-sleeve quality that makes them so memorable.

I don’t know exactly how the final version will turn out, but that’s part of the fun. Just like those hikes in Colorado—step by step, summit by summit—I’ll keep pushing forward, refining, and figuring it out as I go.

Here's the Mars map that I used along with individual screenshots of the various features I selected. There's also an unfinished version of my map :)